Charlie and The Zealot

Have you met The Zealot lately?

He's the bombastic preacher who blasts all other forms of worship.

He's the chess player who is entirely reliant on memorized gambits to win or confound his opponent, and is upset when it's not enough.

He's the middle manager who insists that This is How It Must Be Done. Why? Because this is how it must be done.

What do these zealots share? Circular logic. A vague malaise. A low sense of their ability to create or adapt to new ways of doing things. An inability to improvise, because they have not grasped the deeper principles of their chosen framework and integrated those principles into an overall seamless flow in decision making.

On the other hand, there's Charlie.

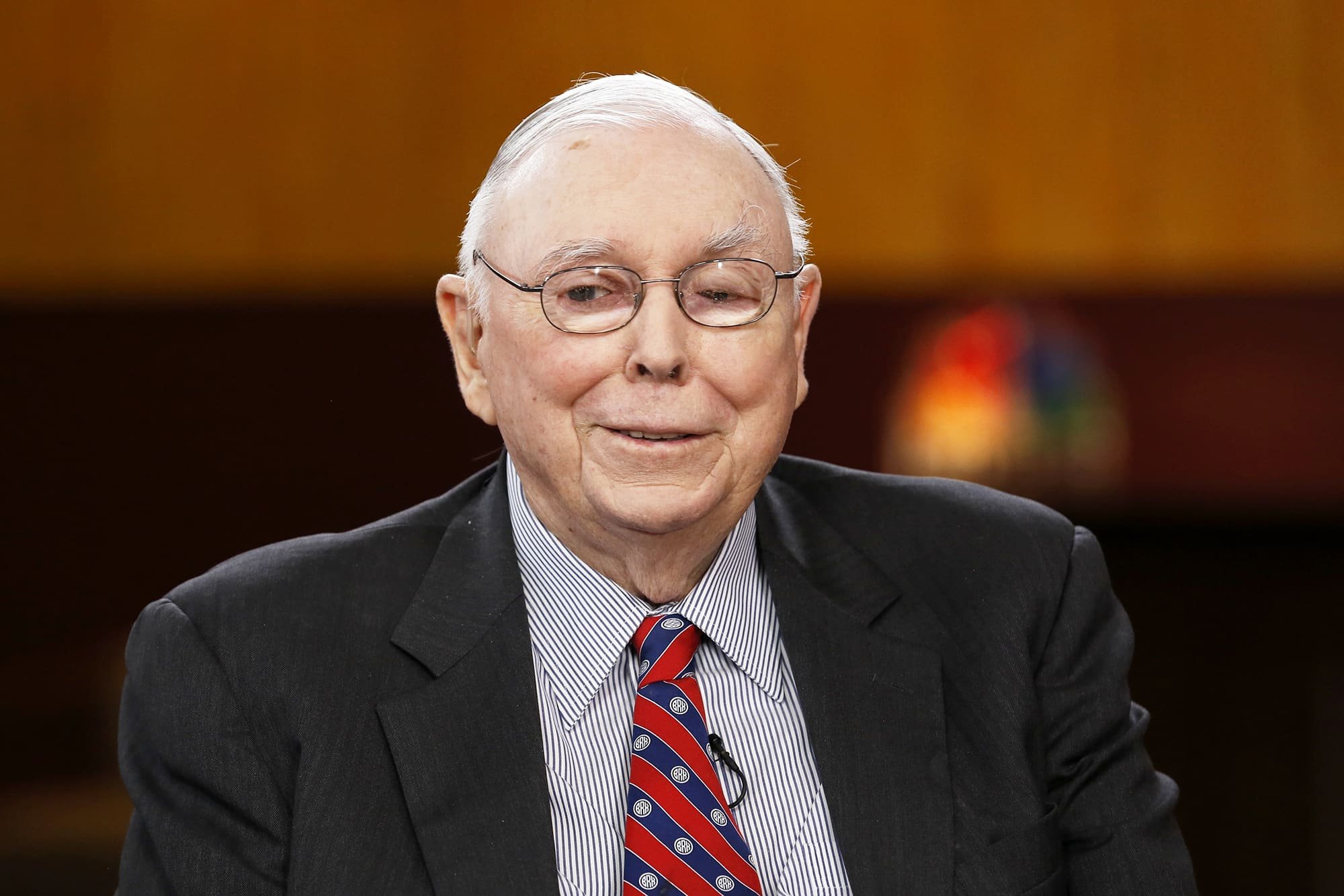

Charlie Munger is a billionaire and philanthropist who is the cofounder of Berkshire Hathaway. Charlie is famous for giving speeches, and being able to think very deeply about a wide range of problems.

Here's the difference between Charlie and The Zealot: dependence.

Charlie knows that every framework has a point of view that can be useful. He also knows that it is not the only way of looking at a situation. The Zealot believes that the way of their framework is The One Way to Rule Them All, and in an extreme case, is dependent on that framework for their entire worldview.

At its most dangerous the belief in The One Framework to Rule Them All becomes core to the identity of the zealot, to the radical and sometimes violent exclusion of other possibilities. More often, I think this zealotry is derived from a person's lack of confidence in their ability to learn, grow, adapt. If you know you can adapt to whatever comes your way, why freak out over one particular framework? If you know that you can learn and figure out new ways to solve problems you don't even have yet, why become attached to just one way of doing things to the exclusion of all others?

There are useful frameworks for every situation imaginable. Each framework is an edification of the best practices in solving a problem from a certain point of view. Best of all, the approach taken by a good framework is not limited to the problem it publicly addresses. An example: The computer science question of whether to "exploit or explore"—that is, to dive in and focus on one result versus continuing the search—directly applies to dating, or the search for a business model in a startup. Combine that search framing with a little knowledge of the paradox of choice, and it's easy to realize that there is a limit beyond which continuing to search is not helpful.

There are infinite examples. The point is that a well-understood framework is useful outside of the domain in which it is primarily applied.

Frameworks are most useful for three things:

A framework is a helpful guide when a beginner is learning how to do something.

A framework establishes a well-developed arsenal of tools, and a certain way of approaching a problem or looking at the world. This point of view can be applied in other contexts as well.

A framework can create a community of people around itself, something bigger than the idea itself. Such a community can do powerful things.

So what does this mean, practically? Learn as many frameworks as possible. But don't just learn to use the framework. Learn why the framework has made its choices—what was the reason for the framework taking this stance? When you run into evidence that seems counter to the frameworks established way of doing things, ask why the textbook way to do it is the way it is. Then look at your reason for doing it your way, and you can then make an informed choice.

I try to do this every day as I continue learning to be a better programmer, but like all good models, this approach will serve you well elsewhere. If you're looking for some material to get started, I recommend reading Seeking Wisdom and some of Charlie's speeches to get started. You can also listen to this recording of Charlie giving a speech on this topic.

I'll let Charlie close this as only he can:

If the facts don't hang together on a latticework of theory, you don't have them in a usable form. You've got to have models in your head. And you've got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life.

What are the models? Well, the first rule is that you've got to have multiple models—because if you just have one or two that you're using, the nature of human psychology is such that you'll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you'll think it does. You become the equivalent of a chiropractor who, of course, is the great boob in medicine.

It's like the old saying, "To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." And of course, that's the way the chiropractor goes about practicing medicine. But that's a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world. So you've got to have multiple models.

And the models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department. That's why poetry professors, by and large, are so unwise in a worldly sense. They don't have enough models in their heads. So you've got to have models across a fair array of disciplines.